The EU Parliament just voted to ban meat names for plant-based foods - why this might be good for vegan budgets

EPT Editorial. Parma Sira, founder of Eat Plants & Travel

You may have read that the European Parliament (EP) recently voted to ban the use of words like “burger", “sausage” and “steak” to describe plant-based foods. The motion, put forward by French MEP Celine Imart argues that such descriptions are “misleading to consumers” and a threat to livestock farmers who say these labels threaten their industry and livelihoods.

The proposal still needs to be approved by the European Commission before we see any changes to restaurant menus, or our favourite vegan products re-labeled in shops, but if backed, vegans in the EU may inadvertently just find that the cost of plant based goods fall.

The Motive: Why the EU Parliament Voted for the Ban

As vegans we've become accustomed to buying meat-adjacent named items like vegan burgers, plant-based steaks and vegan fish. Food manufacturers choose this type of labelling to let customers know what they're buying are alternatives to, and what they are supposed to taste like and mimic.

When you consider vegans are a growing minority in Europe (around 3-5% consistently identify as vegan/vegetarian, with many more being flexitarian) and most arrive at a plant-based lifestyle from consuming animal products - it makes sense to market produce with terminology they're familiar with.

French farmers argue meat-like labelling confuses consumers and misleads them, and many elected officials inside the EU parliament agree (355 voted for the changes, 247 voted against).

The motion argues that manufacturers are deliberately marketing plant-based food to confuse and increase the likelihood of customers mistakenly purchase the wrong products. They're not completely wrong - Beyond Meat, one of the largest meat alternative brands in the world has made no secret of its strategy to position their products alongside actual meat on supermarket shelves.

Is that misleading? Do customers really buy plant-based sausages thinking they're pork?

The reverse is true, I’ve myself accidentally bought meat products, so I know it happens. But does it happen enough for French farmers to blame plant-based food for their struggling industry? It’s unlikely, and there’s a lot more going on there.

Beyond the Burger: The Real Crisis Facing French Farmers

The agriculture industry of France is the largest in the EU, accounting for around 18% of the economic block’s total production every year. It is diverse and world renown for quality and value. Despite its strengths, the sector faces structural and economic difficulties that culminated in the mass protests throughout France in early 2024.

Rising costs, falling incomes, over-regulation and adherence to sustainability standards - are some of the reasons given for the sector’s struggle, as is climate change. Farmers are increasingly impacted by extreme weather events (droughts, floods, heatwaves) which cause crop loss and financial instability.

Placing some of the blame for their struggles on product labelling is seen by many as a desperate attempt to force vegan businesses, part of a much smaller, newer and less influential sector - one that is indeed “eating” away at its profits as more people move away from meat and dairy products - to radically change their business models.

An Easy Target: Why the Plant-Based Sector is Being Singled Out

Anti-vegan sentiment isn’t new, particularly in conservative and conspiracy-peddling circles. We know meat and dairy industries have invested millions to spread misinformation in an effort to discredit scientific evidence of their impact on climate change, and to influence public opinion away from the economic, health and environmental benefits of plant-based diets (Guardian - Inside big beef’s climate messaging machine: confuse, defend and downplay).

Sadly, it’s a battle plant-based companies aren’t able to compete in - the entire global plant-based foods market is worth approximately $50 billion (USD), compared to the $1.5 trillion USD market value of the meat and dairy industry.

Many conservatives, like Celine Imart, consider veganism an attack on their traditions and even though the impact of consumers mistaking plant-based food their meat alternatives is negligible, vegan companies are the easiest target to enforce a change onto.

The dairy industry had previously already successfully lobbied the European Parliament to change the way alternative milk is branded in the EU. For example, oat milk is called oat drink on European shelves.

Luckily, there are some more reasonable voices out there challenging the proposals.

Opposition to the changes

Anna Cavazzi of Germany’s Green party criticised the motion as “useless”, and commented “while the world is burning, the EPP having nothing better to do this week than to involve us all in a debate about sausages and schnitzel”.

Key industry voices in Germany - the largest for plant-based products in the EU, have voiced their opposition (Good Food Institute of Europe), supermarket powerhouses Aldi and Lidl, and even fast food giants Burger King and sausage makers Rügenwalder Mühle have pushed back against the proposal in a joint open letter.

One of the main worries is the banning of certain words that we’re all familiar with, such as sausage, or steak, will make it more difficult for consumers to make quick informed decisions.

What happens if the changes go through

The majority vote at the European Parliament is just the first of a number of steps the proposal needs to pass before being made law.

Next it needs the backing of the European Commision, a politically independent executive arm of the EU, and then the full support of all 27 nations that make up the European Union. A similar proposal was on the table in 2020, but didn’t pass.

So we’re not going to see any changes in the EU anytime soon, but if it does pass what would the changes be?

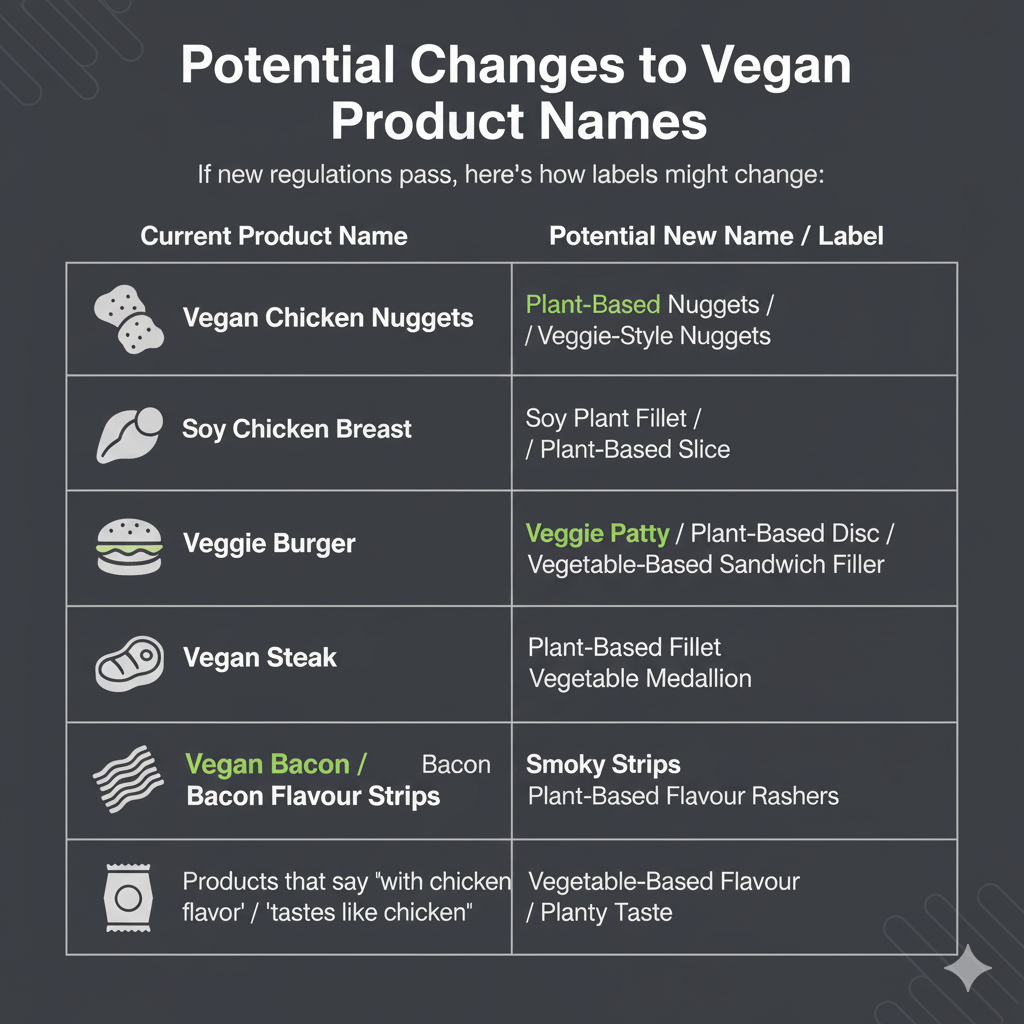

The European Commission’s proposal bans about 29 specific words for plant-based products. These include the names of animals (“chicken”, “beef”, etc.) and also “cuts” (e.g. “wings”, “breast”, “loin”, “ribs”). Another version from the European Parliament goes further, including words like “burger”, “sausage”, “steak”, “escalope”.

We’ll see packaging redesigns, renaming of vegan brands and products, a shift in marketing language and price changes (more on this below).

Here’s a handy guide of some examples of changes you' might see as a consumer:

Our Theory: How the Ban Could Force Vegan Prices Down

Trying to find positives from the proposal, which will have a huge impact in the way we as vegans shop, discover and choose plant-based products to buy, is not an easy task.

To suggest a few supermarket products are responsible for the collapse of the French agricultural industry is an argument without merit and a dramatic exaggeration.

The EU governance process is famously bureaucratic, and many of the 720 Members of European Parliament are from the types of nationalist political parties that deny climate change and progressive ideologies (exactly the people you’d expect to be in favour of these changes).

The chances of the proposal making it all the way through the European Commision and receive the backing of all 27 member states is thankfully slim.

If it does go through, however, I believe we may see cheaper vegan goods in the EU, and here’s why:

Currently, plant-based food is made to be an alternative to meat or dairy products. It’s mostly vegan versions of familiar foods like sausages, steaks, nuggets, and all the other products we find on supermarket shelves. It is branded similarly, and sold alongside the produce it has been created to be cruelty-free versions of. As such, plant based produce is priced in accordingly with their meat counterparts. This despite it often being cheaper to produce, package and create plant-based produce.

If vegan brands are forced to make these changes, and plant-based food becomes independently positioned and marketed with bespoke terminology specific to the sector, then this could be an opportunity to decouple plant-based products from meat price architecture.

Freed from the pressure to benchmark against the subsidised meat and dairy industries, vegan brands may establish a price floor based purely on their fundamentally lower ingredient and resource costs. It creates a new marketplace, one that can set prices more reflective to the costs involved to produce the product, rather being compelled to set prices in-line with the meat variants.

Good news, right?

Well that’s my working theory - in reality pricing of plant-based goods isn’t so simple. Pricing is set due to a number of economic factors, for example - vegan brands are generally small businesses, meaning they don’t have the buying power of larger organisations so the inflated cost of ingredients gets passed down the line to consumers. Although organic ingredients are a lot of cheaper than producing meat and dairy, processed vegan alternatives such as mimic meats require a lot of resources in research and development and speciality ingredients. There’s also the market size, vegan’s are still a minority market, and so the cost of products created specifically for vegans is reflective to the respective demand.

Conclusion: Ethics, Economics, and the Future of Food

When we created Eat Plants & Travel, our aim was to create a global marketplace for vegan brands to sell their products to the vegan community around the world. A platform dedicated for vegan discovery and a mutual consumer-led relationship to help promote, bolster and support the sector.

Working alongside vegan brands, I’ve spoken to so many business owners who feel the costs involved in creating fully sustainably designed, eco-friendly, plant-based products and services is difficult because they don’t receive the same governmental support and subsidies received by other, more vocal and influential sectors. These businesses are created by ethics, not a desire for riches - and feel hamstrung because of this.

Anti-vegan, anti-progressive and anti-sense ideas like the one proposed by Celine Imart only serve to restrict the choices of consumers and prolong practices that are proven to be unhealthy, wasteful, environmentally damaging and cruel.

Instead of trying to revive a failing French agricultural industry by attacking plant-based foods and vegan brands - a move that will do nothing to benefit the industry, and only serve to restrict the choices of everyday consumers - maybe the same efforts and resources should have gone to incentivising, and supporting suffering farmers to move away from animal slaughter and abuse, to more sustainable, eco-friendly forms of farming.

It’s been done before, there are many, many, many examples of how ethical farming can be better for farmers, consumers, communities and the world!

EPT Editorial. Parma Sira, founder of Eat Plants & Travel